The consummate craftsmanship of “West Side Story,” with its matchless ability to weave a solemn narrative through music and dance, still dazzles after more than 50 years. Leonard Bernstein’s majestic score, in particular, is undiminished, shifting fluidly between blasts of syncopated brass fueled by testosterone and rage, and some of the most achingly beautiful expressions of love ever sung. So it’s rewarding to report that after nearly three decades’ absence from Broadway, this masterwork has been given the revival it deserves. Under the knowing direction of Arthur Laurents, the 1957 show remains both a brilliant evocation of its period and a timeless tragedy of disharmony and hate.

Following his emotionally charged “Gypsy” revival last season, book writer Laurents has again dusted off one of his classic shows for a new generation, remaining faithful to the original conception while adding new textures to the drama. Most notable innovation is the choice to translate (via “In the Heights” composer Lin-Manuel Miranda) much of the Puerto Rican characters’ dialogue and songs into Spanish. This heightens the division in the turf war between rival gangs the Sharks and the Jets, and is far less artificial than forcing people to convey extreme passion or grief in their second language.

Audiences with no knowledge of Spanish will hardly feel adrift, however, in that the stakes in this urban “Romeo and Juliet” update are rendered more lucid by the dramatic integrity of the staging. And the feelings of lovestruck joy conveyed in “I Feel Pretty,” or of bitter sorrow dueling with the conviction of the heart in “A Boy Like That,” all but transcend words.

The show’s book has always been secondary to its score, but Laurents efficiently underlines the paradox that the Jets, so threatened by the encroachment of the Hispanic Sharks on their white neighborhood, are only a generation or two evolved from being the kind of immigrant trash they despise. And having their racism amplified through the voice of authority of a sleazy cop (Steve Bassett) further darkens the Shakespearean canvas of warring factions.

From the opening notes of Bernstein’s antsy “Prologue” and the first images of original director-choreographer Jerome Robbins’ iconic moves, with finger-snapping, low-hunching gang members darting in and out of tenement windows and off fire escapes, “West Side Story” comes at you with a familiar rush. But any sense of kitschiness that might arise from watching a dance style that’s been imitated and parodied everywhere from Gap commercials to Michael Jackson videos to “Flight of the Conchords” is soon erased by the bristling confidence and economy of the storytelling. Characters, mood and conflict are established in minutes with barely a word spoken.

As is often the case with “West Side Story,” finding a male cast able to meet the balletic demands of Robbins’ choreography (reproduced by Joey McKneely) while convincingly portraying rough-and-tumble greaseball gang members is a challenge. The squeaky-cleanness of the guys here does take some getting used to, but the agility and youthfulness of the male ensemble soon outweighs those concerns. Cody Green is suitably intense as take-charge Jets leader Riff, Curtis Holbrook channels tightly wound aggression and volatility into his lieutenant Action, and George Akram’s razor-sharp moves and natural magnetism stand out as top Shark Bernardo.

The trickiest role is romantic lead Tony, who is required to scale impassioned heights while retaining traces of the toughness of a former gang member. Matt Cavenaugh (“Grey Gardens,” “A Catered Affair”) may lack some dramatic heft, but his singing has a sweetness and vulnerability that make the central love story soar.

His invaluable accomplice in that department is Josefina Scaglione, an enchanting young Argentine discovery making a knockout Broadway debut as Maria. Combining innocence with real backbone, her tremendously moving Maria has her feet planted far more firmly on the ground than Tony’s; she’s swept up by love but always mindful of its consequences. Scaglione’s operatically trained soprano, with its crystalline high notes, blends superbly with Cavanaugh’s vocals to make “Tonight” and the hymn-like “One Hand, One Heart” sound more exquisite than ever.

Without detracting from the success of a drama that revolves largely around the animus of guys who fight and dance “like they have to get rid of something quick,” the soul of this staging is the women.

The raw purity of Scaglione’s Maria is countered by Karen Olivo’s equally nuanced Anita, a tempestuous spitfire who gets the show’s best number in “America.” Responding to Jennifer Sanchez’s paean to their homeland with withering scorn, Olivo nails Stephen Sondheim’s witty lyrics, with their tart dismissal of old-country romanticism, and Robbins’ exhilarating dance explosion, working her skirt and hair like weaponry. But beneath the savvy, smoldering exterior, her Anita is a woman humbled by love, enabling her to respond to Maria’s needs even through her own grief. Olivo is especially heart-wrenching in the near-rape scene in which Anita attempts to warn Tony he’s in danger, a moment still startling for its dramatic realism in a musical context.

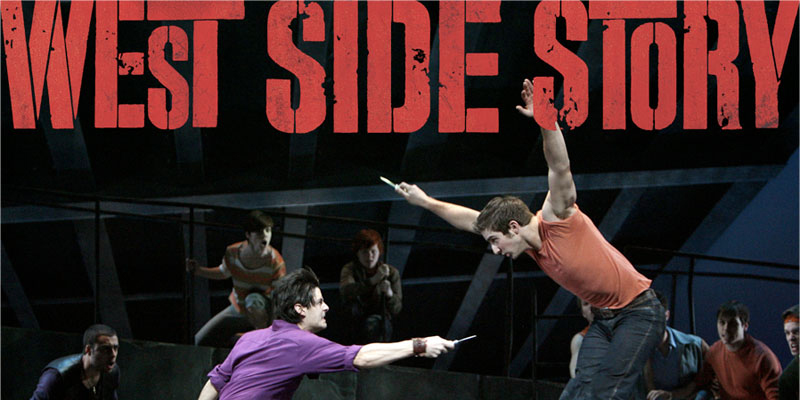

The show’s high points are too many to mention, but the populous “Dance at the Gym” is an electrifying centerpiece. Kickstarted by a whimsical fantasy note as ropes of flowers descend from the flies, the number then moves into a propulsive mambo and from there into the delicacy of Tony and Maria, isolated in their love-at-first-sight minuet. The fatal rumble that follows also is powerfully staged, preceded by masterful merging of five different perspectives in the multipart “Tonight” reprise. When designer James Youmans’ highway overpass looms into view and a wire fence descends to place the entire scene in a cage, the escalation of tension is thrilling.

The physical production is impressive on all counts, from Youmans’ striking, stylized sets to David C. Woolard’s flavorful period costumes to Howell Binkley’s bold lighting, with its supple shifts from celestial planes to brooding semi-darkness to a blinding utopian vision for “Somewhere.”

But the true stars of the production are Robbins’ graceful, endlessly expressive choreography and Bernstein’s score, which still sounds bracingly modern a half-century after it was first heard.

Sure, one could quibble about the odd placement after Riff’s death of the show’s sole comic number, “Gee, Officer Krupke” (the song was effectively flipped with the first act’s “Cool” in the 1961 movie). But every one of these songs communicates something vital and urgent, whether it’s solidarity or love, anticipation or rapture, loss or hope. Performed with a deft balance of percussive fury and caressing gentleness by a robust orchestra under the direction of Patrick Vaccariello, the music is a primal force. It reaches emotional apices more often found in opera than musical theater.